Dear Tim,

The citizens Kalmany are REALLY for privatisation. They’ve so far privatised the Healthcare, Defence, Legal, and the Housing & Utilities sectors, and it’s only been a week of running things! I’d be less upset if I had set-up the logic for the corporations to run their own policies (a little generalised). They also tried to privatise the Legal sector twice. Twice!

Let me first say that, politically, I’m left-wing, so yes I’m biased to this kind of action. But here’s the thing, the logic I wrote for how a candidate picks the policies to take to assembly should mean that they flip back to Nationalising the sector the day after! And then continue flipping.

The reason is simple, and so for this let’s get into my python and allow me to try to explain what ridiculous logic I’ve written to abstract how a candidate picks a policy.

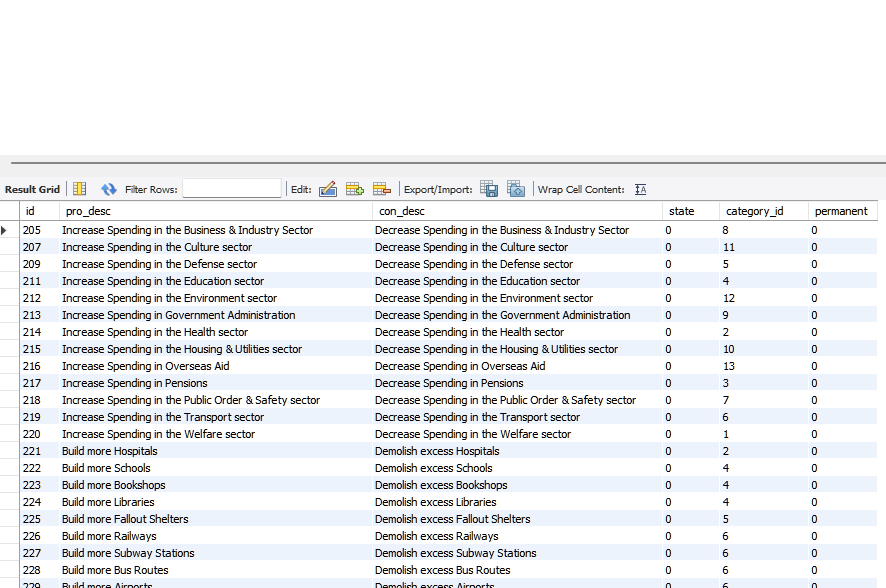

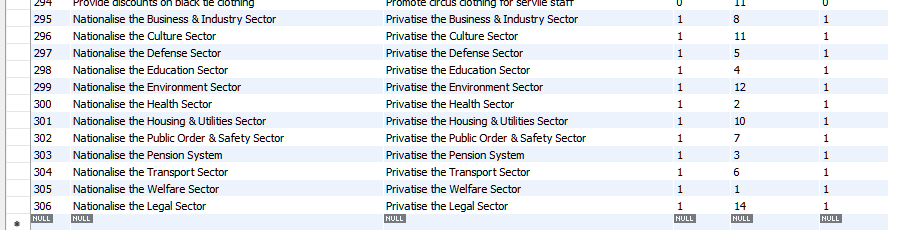

So here we have the table aptly named policies_policy – my data for determining all possible policies that a citizen/candidate can consider/represent in their platform, and then potentially be voted in an assembly AND THEN potentially be implemented. There’s not a lot of information there as you can see – this is because implementation operates somewhere else. The id is obviously our identifier, category_id is how I relate each policy to a government sector, of which there are currently fourteen. Permanent is a simple boolean to help track if the policy, once implemented, remains implemented; this applies to legislative action and privatisation. State tracks the current state of any permanent policies. The pro_desc and con_desc are a little bit of clever logic that becomes very important – each policy has another state that each citizen considers: it’s for or against value.

The FOA value, as my code often makes references to, is basically saying that each policy has a positive implementation and a negative implementation. This is obvious when you read the first few policies; consider that any policy basically has a reversal. You implement, you can un-implement it. So that’s how my code handles a policy, it considers the action as neutral act of doing in this record. Policy 205 will affect the spending in Business and Industry. It’s positive implementation will be Increase Spending and it’s negative implementation will be Decrease Spending. Note that the definitions of positive/negative don’t actually reflect on the end result of that implementation and I could reverse the pro_desc and con_desc if I wanted to.

The nice thing about this representation is it also effectively doubles the amount of policies I have available to a citizen! Now, it gets a bit weird later on:

Some of these aren’t direct opposites. The reason for this is simple; the logic will be the same action, but the description adds more colour to my site! It means it will look like there are more things going on than there really are. It’s just more interesting than someone saying ‘subsidise construction of public transport’ compared to ‘remove subsidies on public transport’. They are also named in such a way where they are repeatable so I don’t end up with a lot of definitive policies that can only be reverted and not compounded.

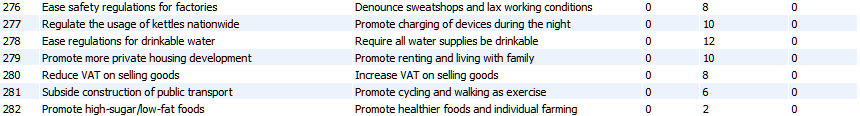

Let me show you the next bit of important data:

This is policies_preferences, a reference table that is used for every calculation of a citizen’s preference, and is a much larger set of data. Looking at it now and thinking about it, it’s quite inefficient and what I should have done is made eight separate tables.

You’ll understand when I get into it: policy_id refers to the id of the policy in the last table, so you can tell this table is a mapping of multiple values. Citizen_attribute correlates to one of the various attributes that a citizen can have: ethnicity, industry, religion, sex, sexuality, agegroup, zodiac. Attribute_value refers to one of the various ids these attributes may be eg. the attribute sex on a citizen can have a value of 1-4. Finally, preference_value – this guy is a value of 2, 1, -1 or -2 and relates to four values: Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, Strongly Disagree. You see where I’m going with this?

This table basically records, for each policy (policy_id), a person with an attribute (citizen_attribute) of this certain value (attribute_value) likes the policy this much (preference_value). That’s it! That’s why there’s a lot of records, it’s almost like a survey and where loyalties for different citizens lie. When a citizen is deciding how much it likes a policy, what it does is it finds, for a policy_id, all the records that match their own circumstances and adds all the preference_values together to get a big old number. It could be +1, they agree with it a bit. It could be +7, they really agree with it. It could be -14, they REALLY disagree with it.

And now the FOA value get’s fun. If I want to determine how much a citizen likes the opposite, I just reverse the sign! They might have a preference_value of +7 for Increasing Spending in Business & Industry. Then that means they have a preference_value of -7 for Decreasing Spending in Business & Industry. It’s a very black and white way to look at it, but it sounds reasonable! It’s believable. They want to increase spending, so OF COURSE they don’t want it to decrease!

So where’s the code that does all this:

def get_affinedPolicies(self):

policies = (

module_session.query(Policy).

join(Category).

where(sqlalchemy.or_(Category.nationalised,sqlalchemy.and_(Policy.id >= 295, Policy.id <= 306))

all()

)

results_full = []

for policy in policies:

affinity = self.citizen.get_policyAffinity(policy)

if affinity != 0:

preference = abs(affinity)

foa_value = affinity/preference

if foa_value > 0:

desc = policy.pro_desc

elif foa_value < 1:

desc = policy.con_desc

policy_data = {

"policy_id" : policy.id,

"foa_value" : foa_value,

"preference" : preference,

"desc" : desc,

"randomseed" : random.random()

}

if policy.permanent:

if policy.state == 1 and foa_value == -1:

results_full.append(policy_data)

elif policy.state == 0 and foa_value == 1:

results_full.append(policy_data)

else:

results_full.append(policy_data)

results_full.sort(key=lambda x: (x['preference'], (x['randomseed'])), reverse=True)

return results_fullExcuse the fact I switch a lot between snake_case, noncase, and camelCase – I can never decide on a convention. I’m the worst.

Anyway, the first part uses sqlalchemy to retrieve all my policies with one caveat; if a policy’s category is not currently nationalised ie privatised, it omits it APART from policies 295 – 306. These latter policies are the specific Nationalisation/Privatisation policies. So even if the category is nationalised, you can still choose to nationalise or privatise.

We loop through each policy for a citizen. The function get_policyAffinity does like I described above – compares the preferences against their alignments (…and some other stuff). If the affinity (how much they like the policy) is not 0 (which indicates they don’t care about it), then we take the absolute value of the affinity as the level of preference. The sign of the affinity is their FOA value. The FOA value determines which description to use and of course which implementation. We just grab the description in case I need to debug. We then collect that data and THEN:

We determine if the policy is a permanent policy. If it is, then we have to determine if the citizen has the policy open to them ie if a sector is privatised, we can’t privatise it again. I don’t care if they like that policy. Their FOA value must oppose the current state of the policy (if I had state as an integer and not a boolean, I could have just one if statement to check if the sum of their foa_value and state was 0 but it’s a nitpick). If the policy isn’t permanent, they can always consider that policy.

We collate these policies into an array and then sort the array by preference. We also chuck a random number in there too so that if they have the same value of preference, they rank in a different order on each run. Just to keep things fresh. And this gets returned as a fully ordered list, with the highest preferred at the top.

This returned array is what I used for determining the ten policies a candidate can have as part of their platform – I just take the top ten and create a mapping between the candidate and the policy, with the foa_value recorded too.

Now. There’s one extra thing I glanced over.

def get_policyAffinity(self, policy):

affinity_value = 0

for affinity in policy.affinities:

affinity_value += affinity.get_affinity_byCitizen(self)

rating_influence = (

module_session.query(ConstituencyRating).

where(ConstituencyRating.constituency_id == self.constituency_id).

where(ConstituencyRating.category_id == policy.category_id).

order_by(ConstituencyRating.assembly_id.desc()).

first()

)

# rating's influence

if rating_influence:

affinity_value *= (1- float(rating_influence.rating)/100)

return affinity_valueOut get_policyAffinity function (I apologise again for my conventions). The important bit is right at the bottom: the rating influence.

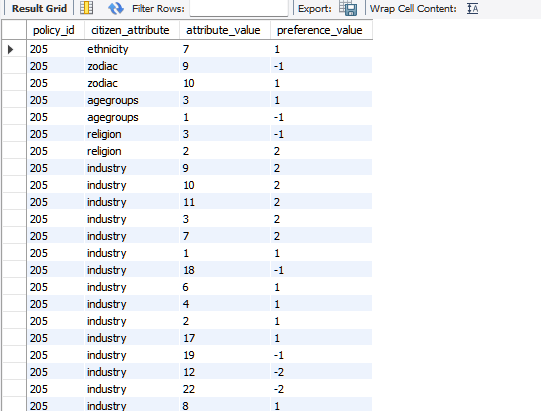

These rating values influence the importance of a policy, but on an ABSOLUTE scale! If the rating for a sector is low, it will multiply the preference by a value closer to 1. If the rating is high, it will multiply by a value closer to 0. This means, a failing sector is more likely to have a corresponding policy brought to the assembly at any implementation – because the citizens want at least SOMETHING done. This is why I think they are privatising so much.

Because, if a rating is low across all constituencies (like Housing & Utilities), everyone will be bringing Housing & Utility policies to the assembly. That’s twenty-four policies. But, I don’t allow a policy to be brought twice to an assembly. Therefore, if they can’t bring their first choice, they’ll bring their second choice and so on… And that has to be the breaking point – if they cycle through enough, they’ll land on privatisation. I don’t have twenty-four policies for each category! I have a hundred policies, but I have fourteen sectors! I have at most TEN per sector! So if ten candidates want to bring Housing & Utility policies to the assembly, then privatisation will be in there!

However, they’re not bringing up Nationalisation, even though the rating is still low. Which means that no one must like nationalising the sectors enough to bump it up above everything else, even with the low rating. I haven’t actually checked what the total preference is for nationalisation which may help determine what might happen.

Not to say its a problem, but it makes the whole experiment very boring IF NOTHING IS RUN BY THE GOVERNMENT.

Power to the people indeed…

Anyway, I hear you’ve made it out of Switzerland and you’re on your way to Germany. Give them my love. The codeword this week is ‘Witterberger’ and you have to say it in the note A#. If they ask you for yoghurt, ask ‘is frozen okay?’ They won’t let you into the Secret National Library if you don’t, and you won’t know either. They’ll just take you to the Non-Secret National Library to fool you. You’ll be able to tell if you’re in the wrong place as the Non-Secret Library doesn’t have a copy of Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman; that’s because I have it. Keep your eyes peeled, they say the Canned Laughter is hot on your tail.

Yours,

Stan

UPDATE: I’m an idiot…

If I had just scrolled down the policies, I would see the issue – the state of all the nationalisation policies are still at 1! The system currently still thinks the policy of nationalisation is off-limits, and that privatisation is still available! No wonder they keep trying to re-implement them. I’ll fix this logic and then we should start to see Nationalisation brought up more. Hopefully anyway,